By Francesco Caruso, MFTA

Where is secularity leading the stock markets? At the present moment there is great uncertainty and confusion, not only among individual investors, in trying to understand the possible developments. In this post I will try to hide my quantitative soul and leave room for the part of me that loves the pure cyclic theoretical research, to shed light on where we are and where we go, through an unusual path: a link between the Dow Theory and Kondratieff cycles.

In his famous Wall Street Journal editorial on January 4th, 1902, Charles Dow assumed that there was an analogy between the stock market and the ocean waves during the cycle of the tides: “Nothing is more certain than that the market has three well-defined movements that are integrated in one another. The first is the change due to local causes and to balance supply and demand in a particular time; the secondary movement covers a period ranging from 10 days to 60 days, with an average of 30 40 days, the third movement is the primary wave, which covers 4 to 6 years. “

Dow made these assumptions in a period that was characterized by large fluctuations in the stock market in both directions, that is late nineteenth century. If Dow had lived at least until the Great Depression (1929-1932), surely it would have added to his theory a fourth wave, we might call the long wave. Beyond the fact of recognizing that the stock market moves in a non-random way – which is a technical analysis’ basic assumption (and for me a deep awareness) – Dow identified the need for a confirmation of two indices, the Dow Industrials and the Dow Transportations: he was (correctly) aware that there must be an economic rationale for the primary signals generated by the stock market.

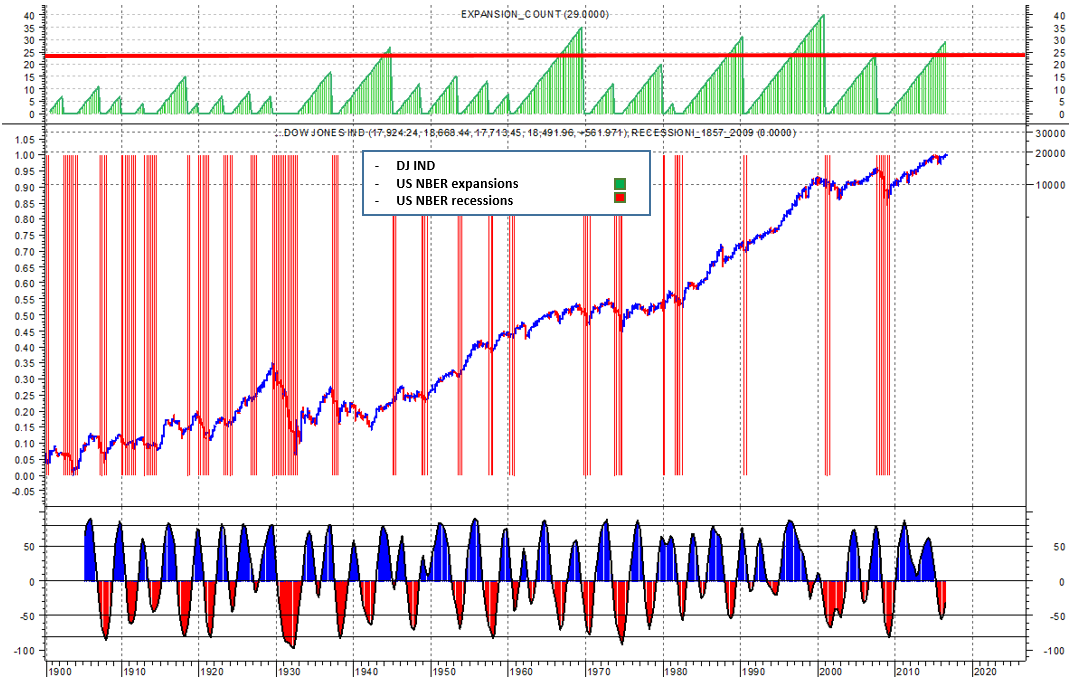

Many pure technical analysts usually bypass this point, because it diverges from the close analysis of prices. The analysis of the markets has evolved from that article (obviously not because of it) into three types: technical analysts, fundamental analysts and academics. As seems to be inherent in human nature, each of these types tend to underestimate and / or neglect the work of others, in order to strengthen their identity. In fact, we now have a lot of data and we know that the secular trend of the stock indices can be severely disrupted, and also that this happens with an impressive regularity – about every 30-40 years: this cycle can be called secular wave or long wave and it was studied also by Kondratieff, with a paramount theory even with all its limitations (now outdated) related to the scarcity of data and difficulty in handling.

A point of cardinal importance that Kondratieff has always maintained is that the long cycles occur independently by extraordinary events, such as wars, famines, inventions and so on, realizing themselves independently, as if they had their own strength.

Obviously, there are still many analysts – especially academics – who believe that the long wave is an imaginary concept. Their argument is based on the assumption that the markets do not have a memory and their rationale is that prices today are totally independent from prices yesterday, last week or last year – and certainly those of 50 and more years ago. Also, since even Fourier and other sophisticated mathematical techniques were not able to positively identify this kind of cyclical, probably there is no cycle.

On the other hand, experiments carried out over twenty years with the non-linear mathematics are beginning to severely undermine the thesis of the non-existence of a memory in the markets. We mention only such as Andrew Lo and Edgar Peters, who in his book “Chaos and order in the capital markets” suggests that the stock market has at least a 4-year memory.

Other high-level academic studies have already shown that the price action is inconsistent with the thesis of the non-existence of a memory and many financial companies are using the nonlinear math to study the markets. Returning to the Dow theory, it should be noted that the logic of confirmation from industrial and transport now is failing, either because significant categories of goods such as services which in fact are not transported have assumed an increasing weight, and because the apparent cause for the long waves of the markets has much more to do with capital formation, debt and currency than with with industrial production.

Even money has a price and that is the rate of interest and also the interest rates over the centuries moved in long waves which are linked to those in the equity markets, although the turning points are anticipated for several years on rates than on the trends of the indices.

The aspect that may create confusion between the long waves of interest rates and the stock market is just that sometimes both move in the same direction, and sometimes they move in opposite directions: this happens because the stock prices have both a growth component and a component that has to do with interest rates and yields of alternative investments.

In the baseline, prices of equity indices are the result of interaction between economic growth, industrial expansion and profitability with respect to interest rates and to alternative investments.

At certain stages, however, the stock markets go up almost exclusively as an alternative investment to the returns that come down on the bond markets: the latter behavior, as history has taught, is more dangerous.

When we look at the evidence of the past centuries, we see an alternation of periods of rising and declining interest rates: these movements have to do with the expansion and contraction of capital and debt. When interest rates and the stock market go up, the component of industrial growth is dominant; in the period following the peak in interest rates, the stock market rises as an alternative investment. During this period, declining interest rates force investors to search for yield and then push them towards lower quality alternative investments, in order to maintain the performance.

Since the shares are riskier and lower quality assets, they become the final alternative, especially when their price – of course in the sense of indices – continues to rise as a result of the increasing flow of money that moves to the stock market.

This concept is easily understandable if you look at the market as a set of connected vessels, where what comes out somewhere must necessarily be somewhere else (cash, bonds, equities, gold and – if you want – the real estate market).

A key point to understand is that all the big waves of deflationary downward stock market took place during the secular decline phase in long-term interest rates. Even if we are going beyond what we know of the past 100-120 years, even looking in the past centuries, it can not be found a single wave of structural decline in equity markets that has taken place while interest rates were climbing. The declining interest rates are a major contributory causes of financial speculation phases, since the income is searched through lower-quality assets: in a broader perspective, therefore, low interest rates are hardly healthy for the long wave of stock markets. Apart from evaluations and other factors and focusing solely on the combination of equity markets (as a litmus test of the economy) and interest rates, we can then divide the stages of the market in terms of secular cycles in four major stages:

1. first phase, which we call reflation (or Kondratieff Spring), is when stock markets rise and interest rates rise in response to improved health of the business cycle;

2. second phase, which we call inflation (or Kondratieff Summer), is when the ascending yield becomes strong enough to be an alternative and therefore a brake on the stock market, which tends to lose value in real terms (as in the period between the 70s and 80s);

3. third phase, which we call disinflation (or Kondratieff Autumn), corresponding to structurally downhill yields and uphill equity markets: this is the stage where most often find fertile ground speculative bubbles;

4. fourth phase, deflation (the Kondratieff Winter), with falling rates and asset prices (stock exchanges, but also often commodities) in lateral cycles or descendants, especially in real terms.

Each of these four phases contains within itself a number of traditional cycles of economic expansion and contraction, that from peak to peak last 5 years on average with peaks up to 9-10 years.

The transitional stages between these four stages, especially the pairs 2-3 and 4-1, are fairly long periods of transition, typically a few years, which serve to restore the synchronization between the various components. The true perception of the transition from one phase to the other historically always comes long overdue, not only among investors but also within economic and financial establishment: just think of how long in the past two decades – certainly until after the crisis 2008 – was dreaded inflation, although for many years and almost everywhere we were in the process of falling interest rates. Now, all latecomers fear deflation, which is now in the final phase.

Of these four phases, the stock markets of the advanced economies have gone through the 80s to 2000 in Phase 3 and from 2000 onwards in phase 4, the Winter: the first who is trying to get out of it is the USA, whose main indices are at new record highs, with rates by the end of QE that are in fact on the rise and in fact are, the short term, not far from the long one (= flattening of the curve). This, mind you, should not give the impression that the US is in a “new cycle”, no doubt, US in the final stage of a typical cycle of expansion among the longest and fetched by the monetary policies of the story, what began in 2009. This makes it clear how little linear is the way in the near future.

Japan and Europe are in fact long overdue: it is still cold, the rates are still frozen at zero or below zero, and then they are still in stage 4, in Winter. But everything changes: thus, for the long-term investor, it is wise to start (quietly, of course) to study a period completely absent from contemporary economic culture and that will struggle a lot to be identified in the coming years: the reflation, whose last example is the post-second World war period and in particular the period between the ’50s and early 70’s. Because it is there, to that strange place that is the Kondratieff Spring, which slowly markets and economies are heading.